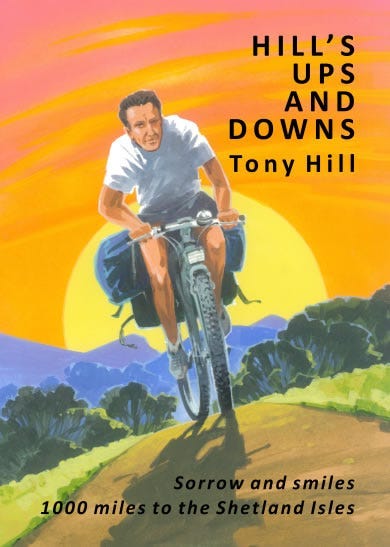

Eps.2 Serialisation of Hill’s Ups and Downs by Tony Hill

Tuesday, July 3rd

I woke with the alarm at 8 o’clock and resisted the temptation to doze. I sorted out my usual black coffee with a couple of slices of toast and settled down to watch the BBC breakfast news. Then I had a second cup of coffee, a shower, a shave and cleaned my teeth before getting into my cycling garb.

I’ve possessed a pair of those snazzy Lycra cycling shorts for a while. They’re supposed to help reduce soreness with the help of an inner leather gusset and they have done the trick on local rides of twelve to twenty miles. Would it work on this mammoth trip though? I’d have to wait and see. I donned one of two tops I’d picked up in a Gloucester outdoor shop the previous Saturday. I’d bought them at the same time as my tent and camping pillow. I was told that this particular type of tee shirt is designed to ‘wick’ sweat away from your body — ‘hmmm, that might well be useful.’ I had chosen a white and a yellow one — bright colours that drivers would hopefully see before knocking me off, or worse still, running me over. From the jungle of shoes under my bed, I selected a pair of my oldest training shoes surmising that these would be the most comfortable. They looked pretty disgusting. The old decrepit trainers had long been relegated to walks through the countryside or used for scuffling along my unpaved, puddle strewn back lane to put the rubbish out. More recently, they were the first choice for building the walls and a patio in our garden. The concrete was still on the shoes to prove it; I did my best to chip it off but failed.

It took ages to pack. I tried numerous combinations and was never really satisfied. The rucksack was too small to carry what I needed but still too big to go on the bike. Eventually I strapped the sleeping bag, tent, waterproofs and flask to the outside of the rucksack to create a cumbersome bundle that could only be picked up with the effort usually reserved for a session in the gym on a day when I felt like a good workout. Kitted up, it just remained for me to get the dead weight securely on to the bike.

I wheeled the machine through my terraced house from the back kitchen, through the living room, along the hall and out of the front door, and parked it on the pavement, propped up against the wall. Back in the hall, I strained to pick up the rucksack. Crikey, even after discarding several items like a Stanley knife, spanners and other possible essentials, it still weighed a ton. Not only that, but the load with its sundries clumsily hanging off it, was cumbersome and getting the bundle on to the bike was a crocodile fight. The bungees, stretched to their full extent, were just as dangerous as any reptile as I tried time and again, to secure the load without toppling the whole lot. The bike just would not stay. I struggled to attach the rucksack but it slid away from me. Then the handle bar lost its tenuous attachment to the wall, and the front wheel left the ground so the bike reared up depositing everything on to the pavement. I was in danger of losing my eye to an escaped bungee hook as I continued to wrestle in vain.

‘What the hell do I do now?’ Worried, I pondered the bike and the bundle on the floor for a minute, understanding that my gaze alone could not solve the problem. Maybe the rest did me good or perhaps it was luck, but as I turned back into the struggle, the next round was mine.

I locked the front door, put the key safely into my bum bag and pulled the laden bike from the wall. Awkwardly I cocked my leg over, making sure to clear, not only the familiar saddle, but also the baggage, piled high and strapped behind it. It was like learning to ride a bike all over again it was so top heavy. I wobbled down the road taking a short cut. As I pulled out on to the main Brecon Road, I didn’t even think about my piles, which was just as well given the lack of serious attention that I had given to my problem. Perhaps, it also had something to do with the one hundred percent concentration I needed to keep my balance, as I seriously started to doubt how far I was going to get on my precarious two wheeled contraption.

Merthyr Tydfil is a bit like a funnel. You can go south (downwards if you were a liquid) towards Cardiff quite easily. However, if you want to go in any other direction you have to climb steep hills. My route would take me east towards Abergavenny along the infamous ‘Heads of the Valleys’ road, the A465. (‘Deads of the Valleys’ would be more appropriate given the number of fatalities that had occurred on this terrible three lane highway.) There was no way that I could avoid some serious climbs but there was a lot of internal debate going on in my head as to which climb would be the least painful. The most direct route was straight up to Dowlais passing the OP chocolate works, but it was ladder-steep. I decided to take the route north, which made a fair detour, but one with a gradient I hoped I would be able to pedal. As I teetered through Cefn Coed, I passed Ken’s house and noticed Yogi’s car was parked outside.

‘Shall I drop in for a coffee?’ I had been with Ken and Yogi the night before. Was there anything new to say? I had only pedalled a mile. Now was not the time to stop, so I passed by, feeling the pressure on my legs as the embryonic gradient made its presence felt.

‘Hell, this is hard work,’ I thought, as I approached the Heads of the Valleys. Now, suddenly, I had traffic to contend with. Not just lots of cars but heavy lorries too. As I ploughed on up the hill I became aware of the passage of time. This was taking an age. Soon the hill became too steep to cycle and I dismounted in inelegant fashion. Now, pushing my top heavy overloaded mount, there were frequent heart-stopping moments as exhaling trucks thundered inches from me. As they rumbled away, leaving me in a wake of dust, I realised that the traffic calmed bumps of the ladder to Dowlais would have been the better option after all.

‘Too late now,’ I thought, as heat from my exertion and the strengthening sun caused the sweat to flow and my sunglasses to creep irritatingly down my nose. Eventually, I reached Dowlais top. Only two and a half miles from home, this was the first milestone. The sun was really blazing by now and I called in to a ‘Happy Diner’ to get a canned drink. The drink didn’t last long and I was off again — burping along the Heads of the Valleys road, so called because it chops off the tops of many of the former mining valleys: the Taf, the Rhymney, the Sirhowey (of Kinnock fame) the Ebbw. The ride was now a long haul, slow motion roller coaster. My progress faltered as I dismounted to shove the bike up the sides of each young valley, but picked up as gradients flattened and I could pedal towards the tops of the watersheds. Then, best of all, came the freewheel down into the next valley.

There is something special about coasting downhill on a pushbike. For me, it’s got something to do with the free ride — no petrol, no diesel, no engine noise and the opportunity afforded to feel the rush of fresh air with unimpeded panoramas. No fly-stained windscreen, no rear view mirror, bright red shiny roof pillar viewed from inside the car cockpit. No radio or booming bass CD and even in the rain, no squeaky wipers. No smell of Halford’s lemon air freshener, just the scents of the outside world — that place that exists beyond the inside that we so naturally gravitate towards for the bulk of our lifespan. It’s the same feeling of freedom gained from sailing, windsurfing or walking. I find a special pleasure in getting there under my own steam. That’s not to say that in the past I haven’t been rather pleased with engine power. And, Cherie always preferred it.

Once we had gone sailing in our little twenty-three foot yacht on Milford Haven. The name of the boat was ‘Halcyon’ and it was indeed a halcyon day, as we navigated, under sail, between the buoys that picked out the main shipping channel — red cans for port and green cones for starboard. The river itself fills a valley that once was land and perhaps the word ‘river’ is misleading, because even five miles from the sea itself, when the tide was in the water stretched a distance of quarter of a mile from bank to bank. There was plenty of space for all manner of craft — big yachts, small yachts, gas-guzzling motor cruisers — even the Pembroke Dock to Rosslaire ferry. And just a quarter of mile downstream, leviathan oil tankers from all over the world tied up on jetties the size of Brighton Pier. Yes, there was plenty of space out there.

Cherie sat opposite me, ‘Want anything to eat?’

‘Dunno, what have we got?’

‘Cheese, biscuits, sandwich. I’m not cooking while you’re sailing.’

Cherie didn’t like sailing. She asked, ‘Do we have to use the sails?’

‘Yes, we do!’

‘I don’t like it when it tips over.’

‘It’s not tipping — it’s supposed to lean over.’

‘Well I don’t like it … and what’s the point anyway?

‘What’s the point in having a sailing boat if you don’t use the bloody sails?’ I retorted gruffly.

She carried on, ‘We’d get there a damn sight quicker if you just switched the engine on. Why do we have to zigzag all over the place? Why can’t we just go in a straight line?’

‘But it’s not the same,’ I insisted for the … goodness knows how many times I had tried to explain. ‘And I can’t hear the radio if anyone wants to call us up … and anyway, that’s what’s sailing’s all about!’ I was exasperated. We’d had this discussion so many times before.

Cherie was unconvinced, ‘I don’t see the point.’

But this day I was having my way and the engine was off.

Dark blue, the river reflected the sky and was hardly ruffled by a gentle breeze that was powerful enough to fill the sails and drive us, tacking across the waterway towards the sea and the village of Dale, some four miles to the west. I didn’t know the river that well but I was aware that if we were to helm the boat out of the navigation channel, there could be problems. I explained.

‘We don’t want to go outside these buoys, Cherie. It looks OK but we could get stuck on a mud bank. And, there’s all sorts of wreckage under the surface once you’re out of the channel.’

There followed a pensive silence from Cherie. We hadn’t owned the boat for long, and I had never received any formal training. Consequently, I hadn’t completely mastered the art of tacking (turning the boat into the wind). Nevertheless, I pulled the manoeuvre off most of the time and therefore saw no need to get out of the shipping channel when Cherie alerted me with a startled cry,

‘Tony! It’s the ferry!’ There was real concern in her voice but I was used to her getting nervous on the water and I blotted out her pleas and refused to turn the engine on.

‘Don’t worry — no problem,’ was my captain-like answer. Our boat was headed out of the channel and away from the ferry — and it was miles away in any case. I was more afraid of running aground or hitting something underwater as we headed for the shallows. We needed to tack back into the waterway.

‘Ready About!’ I pushed the tiller away from me.

‘Tony! Tony!’ Cherie’s voice punctuated each part of the manoeuvre. ‘Lee Ho!’ I called, swapping sitting positions with a reluctant Cherie as we criss-crossed to sit on opposite sides in the cockpit. The boat steered obediently back towards the centre of the river.

‘Tony — what the hell are you doing …’ Cherie’s head craned forwards, her eyes bright like a startled animal … ’the ferry, Tony … THE FERRY!’

‘Cherie!’ my voice was raised and assertively crisp. ‘Don’t panic. I’m going to tack again now.’ It was just a case of tacking to port to bring us back towards the green cones and out of the shipping channel.

‘Ready about … Lee Ho!’ Confident Captain Hill shouted the time-honoured commands once more. Push the tiller away, neatly swap sides again and pull in the sheets — easy-peasy. The boat obeyed and swung to port, now facing directly down the Haven. Still turning a little more, we headed out of the channel to relative safety. I glanced coolly over my shoulder and noticed how close the ferry now was. Cherie was silent but her face was set in inquisition, ‘Why don’t you just stick the engine on and save all this hassle.’

‘Blimey, that thing must be moving …’ I kept my thoughts to myself, not wanting to acknowledge that Cherie’s alert might have had some worth after all … ‘that ferry was a good half a mile away just now.’ Suddenly, my secret relief was interrupted. The foresail filled with wind on the wrong side and our little boat turned back towards the ferry.

‘Tony, you’re heading straight for it,’ Cherie’s voice surprisingly now quieter and resigned.

‘Quick, turn the engine on!’ I relented at last. I was shocked. I couldn’t believe how fast the ferry had moved. It was upon us. We both jumped as a loud horn boomed across the water. Who said power gives way to sail? Cherie pushed the starter and the engine turned over … and over … but nothing happened.

‘Keep going!’ I yelled.

Cherie kept her thumb on the starter screaming at me, ‘I am, I am!’

The horn boomed again. This time it didn’t stop as it droned ominously louder. Now, I was scared. ‘Throttle, I need more throttle.’ I’d forgotten to push the throttle lever forward in my fluster. The ship bore down on us like a slowly moving block of council flats. The swoosh of the ship’s bow wave now mingled with the siren horn and the sound of my name as Cherie desperately screamed it. A wall of white paint blotted out the familiar riparian colours of the far bank, and I could see hundreds of rivets neatly lined up on the ship’s hull.

Suddenly, we felt a shudder as our engine spluttered into life, the clanking for once muted. At last, we reclaimed control of the steering from the wind. Pulling ungracefully away from disaster, the sails flapping uselessly and the boom confused, I cowered and averted my gaze from the onlookers aboard the ferry. Cringing as the Captain and crew swore inaudibly at me from the bridge, I could feel their eyes boring into me.

‘I told you to use the engine, Tony.’ There was no getting away from it. Cherie was right. With the crisis over, we turned the boat into mid channel once more and I chanced a look at the ferry, now small again as it started its turn towards the terminal. The sheets now in their cleats and the sails set, I cut the engine.

‘Why don’t you leave the engine on now, Dear?’ Cherie’s familiar request repeated for the umpteenth time.

I meekly resumed my anti-motor argument, ‘Look, the ferry’s gone and we’ve got the river to ourselves again.’

Cherie didn’t answer. She disappeared below and called out through the companionway, ‘What did you say you wanted to eat?’

‘Cheese and biscuits,’ I said, ‘and what about some wine?’

‘Good idea — not while we’re sailing though.’ With this, she won the debate.

I reluctantly started the engine and spent the next five minutes de-rigging the sails. Motoring down the river in the sunshine, we sipped our wine as the engine thudded on beneath us, and talked about the pig roast and the friends that awaited us on the floating pontoon just off Dale. I was aware of how frightened Cherie must have been as I incompetently aimed our boat on a collision course for the ferry.

But as far as Cherie was concerned, it was already in the past. She knew I had learned a lesson and made no more of it. She used her magic switch and the whole trauma was gone in an instant. Did I ever tell her how much I loved that about her?

It was only after Cherie died that Isobel, her sister, told me just how much she had disliked sailing. Yes, she liked tiddling along and enjoying the scenery, or sunbathing in the nude out at sea, far from prying eyes. And she loved to stop off for a bar snack at one of the many pubs along the river, or beach the boat for the night at some remote inlet. But the rest of it — the real sailing — she only went along with it for my sake and she rarely complained. And never even reminded me again of that day, the day that wonderful fifteen horsepower boat engine prevented certain disaster.

As I shot down towards Ebbw Vale, the folly of not wearing a helmet struck me. But then I never had. I had always taken the risk of incurring head injuries for the pleasure of a ‘Wheee’, the affectionate term I coined for freewheeling. On my way to work there are six ‘wheees’. I mused what the opposite of a ‘wheee’ might be. ‘Wheeze’ was the obvious choice! And I was in line for a wheeze as I began to climb to the highest point on the Heads of the Valleys — 1350 feet. It wasn’t long before I had to dismount. Progress halted to a trickle again, time stood still and my mind wandered to the awesome task ahead of me.

‘Anything is possible.’ How many times had I heard that before? It was just a case of being absolutely determined, focussed and single minded, with a heavy dose of working really, really hard — then anything was possible. As I climbed onwards, these thoughts gave me inspiration and filled me with confidence. Of course I could get to the Shetlands on my bike! Then I argued with myself: For all the famous success stories, do we ever get to hear about all the lowly unsung failures? Never mind the monumental ones like the inability of Titanic to complete its maiden voyage, or the Charge of the Light Brigade. Or, one of my own personal failures: being a member of the world’s worst football team, as a teenager, Cornelly United under 15’s. We lost most games, the worst one being a 24–0 drubbing.

As I reached the slow brow, I realised that a big ‘wheee’ was coming up, probably the best part of four miles down the Black Rock Gorge towards Abergavenny, and I had become aware of a wobble in my front wheel. This was nothing to do with the general instability of the bike but something technical that could undo me. I reached a burger van just past the signposted ‘highest point’ and pulled in to buy another can and investigate the fault. It occurred to me that the tyre might not be sitting correctly on the wheel, probably the result of me changing it the day before. I had an unhappy knack of doing jobs that resulted in making things worse. I decided to deflate the tyre, squiggle it about a bit, then pump it back up. This was pretty close to the limit of my technical expertise and I went about the task with enthusiastic pessimism.

When it didn’t work, I knew I’d have to find a bike shop in Abergavenny and hope they would help me on the spot. If they couldn’t, I might be held up for some time.

‘Damn it,’ I thought. ‘I’ve only gone eighteen miles.’ But, surprisingly, my simple ploy worked and I hazarded downward glances at the front wheel to confirm the fact as I dangerously picked up speed down the long hill to Abergavenny.

The market town was busy and it wasn’t clear from signposts where I was supposed to go. I stopped and asked some passers-by who gave complicated instructions that I half managed to memorise and follow. After some confusion, I ended up where I wanted to be — on the back road from Abergavenny to Ross via Skenfrith.

The B4521 quickly turned into a real stinker, at least for cycling. Most of the time, I was forced to walk as the road rose and fell steeply like the trace of a cardiograph and sweat beaded down my cheeks and along my arms to drip off my elbows. I was beginning to realise that cycling with such a heavy load for so many miles was totally different to anything I had experienced before. Usually, I don’t have to get off to walk. The gearing on a mountain bike is so low that it’s almost possible to go up a wall. Skinny kids with bare, bony torsos trying to cover their spots with a suntan, demonstrate this in the parks and back streets all the time — pedalling up impossible inclines and pulling wheelies like circus clowns on unicycles. Dropping down to these super low gears does, of course, mean that you have to pedal much faster to keep up any speed.

Probably because they have never experienced anything more extreme than a Sturmy Archer three speed system, lots of ‘born again’ middle-aged cyclists fail to understand the gearing. Their brains get used to going at a reasonable lick on the flats and down the hills. When they encounter an uphill, they drop down the gears but compensate for their lack of speed over the ground by sub-conscientiously pedalling like bill-ee-o. This has the effect of instantly wearing them out so the next time they get on a bike, it’s to demonstrate the quick release saddle adjustment to a prospective buyer at a car boot sale.

I generally just accept the fact that I’m going to go a lot slower up hills and I keep my pedalling rate constant. But now with my burden, it dawned on me, ‘What’s the point?’ The bike computer told me I was covering three miles an hour. I could walk at that speed, give my backside relief from the saddle, and rest my pedalling muscles as I employed my walking ones.

Under normal conditions, another option would be to select a higher gear then come off the saddle to bear down with my full body weight on the pedals, but with the heavy load I was carrying and its high centre of gravity, the natural sideways movement of the bike when ridden this way would have had me off in seconds. I also had to consider how far I had to go. I couldn’t afford to ‘go for it’ as I normally would. I had to conserve my energy and be kind to my sinews and muscles. On this road, there were numerous hills but they didn’t last for long, so I continuously alternated between freewheeling and walking. It didn’t bother me that progress was slow. I had so far to go there was absolutely no point in rushing. In fact, there were a few sharp reminders from Cherie. I was hit by a strong feeling that she was following me, as she so often did when we went out riding on our bikes.

‘Hey … you! Slow down, it’s not a race!’

I couldn’t resist stopping and looking over my shoulder. And there she was, her hair auburn, long and wavy and wearing a pink tee shirt with a neat little pair of powder blue shorts that capped her toned brown legs. She was as I remembered her in the early days and she was pushing a crock of a bike that my daughter had pulled out of a skip years before. At five foot four and what Dorothy Perkins would call petite, I was surprised how strong she could be. She hadn’t ridden a bike for years when we decided to cross the Brecon Beacons for a picnic one summer’s day.

No plan was made as to how far we were going, but we ended up eating sandwiches, drinking red wine and dipping our toes into the cool waters of the Talybont Reservoir, on the other side of the mountain range, nearly twenty miles from home. The ride back felt like sixty miles, but Cherie ground endlessly at the pedals and I felt guilty that I had allowed her to come so far on such a boneshaker. And, of course, when she called out to me, I did slow down — I always would. I never raced against her and there was no question of competition between us. We always worked together and we complimented each other in most everything we did. But, she was so physically capable that I sometimes failed to notice that I was forcing the pace beyond her comfortable limit.

By one o’clock the sun was reaching its zenith. I hoped there might be a pub where I could get a drink and something to eat, but this back road was quiet. There were a few houses dotted along the route but no real settlements. Occasionally a car passed by. As a geography teacher, I would tell my kids in school that in areas like this there were an insufficient number of people (or ‘threshold population’) to sustain local services like schools, shops and, most importantly, pubs. But, to my surprise, as I rounded yet another backwater bend, I saw a sign advertising afternoon teas.

I have seen these enterprises in remote spots before. When you’re in the car looking for a pub, they fleetingly make you think you’ve found one. You see the sign, assume it’s a pub, and it takes a second or two before you equate ‘Afternoon Teas’ with ‘Unlicensed’ and drive on. But this was a sellers’ market, so I dismounted, wheeled the bike up the drive and manoeuvred it to awkwardly rest against the wall. The place was really just someone’s house with a pretty garden and a country kitchen. I ambled back to sit at a small round table that wobbled on uneven paving slabs and spent ten minutes collecting my thoughts and relaxing amongst the summer fragrances of the garden. At last, my food arrived and I was impressed. Substantial cheese and plenty of tomato, on expensive bread, served with a thoughtfully arranged side salad, made even more impressive by the ridiculously small bill.

As I munched away, an elderly couple moved across my line of vision. The gentleman wore a brown sports jacket and, typically for his generation, a collar and tie. He was broad shouldered and tall and appeared to be in good shape. By comparison, his wife, in an old lady’s checked cotton dress, was tiny and very frail with grey wavy hair and no weight in her face — should looked as if she would fall apart in a strong wind. She stooped as she walked and they both wandered aimlessly debating where to sit and whether the place was serving, given the apparent lack of staff. The sight of me eating must have kept them hanging around. I had finished my meal and I thought it only polite to address their quandary.

‘They are open. Try looking in the kitchen.’

They both thanked me and went over to seek the chef. When they returned, we resumed our conversation. Incredibly, the man was in his ninetieth year and his wife was five years younger. He had been in the police force, but, after his retirement at the age of fifty-five, he had travelled the world as a judge in sheep-showing competitions. He had, in fact, been officially retired for thirty five years, and I marvelled at his good fortune. Then, three coincidences emerged.

‘Where have you come from today?’ I asked.

‘We’re on our way back from Southampton, where we’ve been to see a friend of ours coming in on one of the BT Global Challenge boats.’ The friend had come in on the last boat, the ‘Isle of Man’, and, as a result, they had been kept waiting until the next morning for its arrival. The other boats had come in the night before.

I told them, ‘My sister-in-law is Chey Blythe’s personal assistant.’

They already knew that the BT Global Challenge was the brainchild of the famous ‘Round the World yachtsman’ and we chatted about the race for a while.

Then, a second coincidence:

‘Where are you going?’

I sheepishly replied, ‘The Shetland Islands.’

I didn’t really feel confident that I was going to cycle that much of my journey and at this point on Day 1, it seemed an awful long way away. I felt embarrassed and a bit stupid but the gentleman boomed,

‘That’s absolutely marvellous! My word, you must be fit.’

I was heartened that they acknowledged the distance factor with some respect rather than derision, and they went on to tell me that they had only returned from the Orkneys (the Shetlands’ nearest neighbours) themselves a few weeks ago.

They asked me, ‘Are you going to Orkney as well as the Shetlands?’

‘Yes.’

‘What ferry are you taking?’

My planning had not been rigorous to say the least, and my ferry options had been weighed up from evidence provided by my ‘AA Road Atlas of Great Britain, 1999’, in which the ferry routes are shown as dotted lines. The only dotted line on the map was from Scrabster, a few miles north east of Thurso on the north coast of Scotland, to Stromness on Orkney, so that was my answer to the gentleman and his good lady.

After a short pause he said, ‘Do you know there’s a foot ferry from John O’Groats to the southern tip of the Orkneys? It’s not as far, it’s cheaper and, what’s more, they’ll let you take your bike on?’

‘That’s very interesting, I didn’t know about that,’ I admitted. I thought to myself, ‘This is incredible. ’

I would have liked to have gone to John O’Groats, even though I hadn’t wanted to do the Land’s End to John O’Groats thing. Sticking to my original Scrabster plan, I would have taken the A9 to Thurso missing out John O’Groats, as I cut off the northeast corner of Scotland. Who would have thought, on a sleepy back road on Day One, that I would glean such useful intelligence?

The third coincidence came up when I asked them where they were headed.

‘We live in Cheshire, but we decided to head back via the scenic route through Wales.’

The elderly lady spoke up, ‘We don’t come from Cheshire originally you know, we’re from Liverpool.’

‘Whereabouts?’ I enquired.

‘Aintree.’

‘Wouldn’t you know it?’ I thought. ‘Small world.’ Aintree was just up the road from Cherie’s parents, her birthplace, and the home she knew up until the age of seventeen. I kept my connections with Liverpool to myself and said goodbye to the couple leaving them to eat their sandwiches.

Feeling happy with the unexpected human contact, I hauled the bike off its staging post wall, mounted, and pedalled off in an easterly direction for Skenfrith. The road continued its serious spurts of ups and downs and I jumped on and off the bike getting ever more used to the routine. An hour later I was in trouble. The first twinges of cramp attacked the muscles in the back of my left leg just above the knee. I immediately dismounted. I knew all about cramp from years of playing football with short legs in grass that was too long. I knew that a minor seizure was a warning but if I carried on I would get a major attack. If that happened, the muscle tissue would be scarred and it would take weeks to heal — it would mean the end of my trip. But, this was an embryonic seizure and I hoped I had acted in time. As I walked the up-hills and the flat sections, I only risked the saddle to freewheel downhill.

I could see from my map that I still had a few miles to go before I reached Ross so I decided to rest, thinking my muscle would be able to recuperate. I pulled on to the right hand side of the road where an access road to a farm had created a rare piece of flat ground that broke the line of bank, ditch and hedge. Better still, it was grassed. Beyond the wire fence, a few horses were grazing in the sunshine and one started to head towards the fence but, I took no notice and purposefully avoided holding out anything that might have been construed as food or friendship. I leaned the bike against the fence and removed my waterproofs from the back rack to serve as a pillow.

In the deserted sunshine, on this green country road, I lay down to sleep. Just as I was dropping off, I was stirred from a semi slumber by an engine in very close proximity. A woman in a towering Range Rover passed alongside me — I think it was her lane. I smiled what I hoped would be a friendly smile that was thankfully returned. After that I couldn’t drop off to sleep. Although I tried for quarter of an hour, it occurred to me that I had had more rest time than a cramp struck footballer in a cup final facing extra time … and they always seem to manage to shake off their seizures. I’d probably taken half an hour all told. I would just take it easy for the rest of the trip to Ross.

I told myself, ‘Don’t put any pressure on the pedals and, if in doubt, get off and walk.’ But as soon as I started back I knew that this was not cramp.

‘No, no, no! … I’ve done something here.’ It now felt like a hamstring injury. I was devastated. I just couldn’t believe it. I’ve had aches and pains from cycling before, but I have never injured myself. In my planning, I hadn’t even considered the possibility of a muscle or ligament strain — tiredness and fatigue maybe, but not this, not on Day One! I sat astride the bike, cupped my face in my hands as I closed my eyes and took several deep breaths…

‘What now?’ After a minute or so, I got off the bike and dejectedly started to walk — I couldn’t cycle any more.

‘On Day One — unbelievable.’ I repeated the words over and over. ‘You’re too old for this Billy Boy — face the facts.’

Cycling to the Shetlands sounds fine when you say it. It’s as if you are going to do it, but it disguises the reality of how hard it really is. It’s not even as if, like Ian Botham when he walked from John O ‘Groats to Land’s End, I had a support entourage. No posh hotels, hearty suppers, hot baths or foot massages from expert physiotherapists. Not even any companions.

‘Argggggh…’ I continued cursing as I shoved my bike along, my spirits sinking with each step. At last, the B road ended in a T junction as it hit the main A49 and I turned towards Ross, hoping to find a camp site soon.

Just a mile down the road, and two miles from Ross I came to a place that was not really a place, Peterstow and no more than a small collection of houses with a post office.

I bought some assorted snacks and a drink and asked, ‘I wonder, are there any campsites around here?’

‘Yes, just down the road.’ My spirits were slightly raised and then given a further boost.

‘You’ll see the pub on the left, the Yew Tree.’ A pub, eh? Things were looking up in a relative sort of way. I cruised down the hill towards Ross, and absent-mindedly sailed straight past the pub. After backtracking fifty yards, I wandered around the outside of the pub. It was now quarter to four and there was no sign of life except for the sound of a radio somewhere in the building. After about ten minutes of milling about, knocking knockers, ringing mute bells that may have worked out of ear shot, and politely shouting, I eventually found a thin man that looked as if he had just got out of bed, and struck a deal — £4.00 to camp for the night.

Wheeling the bike over to a portakabin toilet/shower block I pitched the tent close by, thinking that a guaranteed walk to the loo in the middle of the night would be a lot easier. It didn’t look as if I would have to face the flip side of that coin: many other merry campers doing the same thing and keeping me awake. The camp site looked quite deserted. There were no other tents, and, although there were quite a few caravans, most seemed to be unoccupied.

Now was the time to put up the new one-man super- duper tent I had bought in the Gloucester outdoor shop the previous Saturday.

‘What exactly are you looking for,’ the helpful sales woman enquired.

‘I’m after something extra light weight because I’m touring on a mountain bike.’

I continued proudly, ’But, it needs to be 100% waterproof; I’m headed for Scotland, you see.’ She gave me a knowing smile and nodded her head repeatedly like a doctor when he recognises the symptoms you are describing.

‘Terra Nova I would recommend, yes, Terra Nova — definitely. There’s the two man version over there.’ She pointed to a yellow and green tent that had been erected on the shop floor carpet. ‘We’ve got the one-man version in stock too. Would you like to see it?’

‘Yes, please.’ She was very helpful and a model salesperson. Within minutes, she had put up the tent and given me a list of do’s and don’ts. I was impressed.

‘Great, how much is it?’

‘They’ve used these all over the world, even on Mount Everest.’ She appeared not to hear but went on to fill me in on the technical aspects of the poles.

‘They’re made of titanium. They look like ordinary tent poles but they’re not. These won’t break in a gale.’

I sensed an evasion strategy and guessed that this Mount Everest tent with poles stronger than bridge supports was going to cost me.

‘How much is the tent?’ I asked quietly.

The saleswoman had not finished with the poles: ‘They’re made in this country, not the Far East, they look the same but these are much better. These are the ones the mountaineers use. I wouldn’t take the risk …’

‘Yes,’ I interrupted to let her know I understood. But, she wasn’t ready to answer the ultimate question yet.

‘It’s the same with all outdoor equipment, you get what you pay for…’ Suddenly, her clichéd delivery had become blatantly text book.

I cocked my head, smiled and let my face repeat, ‘The Price?’ It was time to talk money.

‘Two hundred and fifty pounds,’ she said nonchalantly. I wasn’t too surprised though and I made no objections. If I was going to get stuck in the middle of the Grampian Mountains in a hurricane, I wanted to be sure my home wasn’t going to fly off into the North Sea. I just wished that I had thought the same way about my baggage and bought some decent panniers for my bike.

And the tent did go up ‘in no time’, just as the sales girl had demonstrated. I washed the day out of my breathable tee shirt and underwear and proudly rigged a line to dry them between my bike and the tent. It was now eight o’clock and I needed some food. I was still morbidly dejected about my leg injury but was slightly cheered by the fact that I couldn’t feel any pain or even discomfort as I walked. Still, I thought it was a good idea to catch a bus into Ross and give my leg a chance to rest from cycling. It had been ages since I had caught a bus and I wondered how reliable they were these days. My reservations were confirmed as I waited over half an hour. I had arrived at the stop ten minutes early having gleaned the timetable at the campsite house beforehand. The driver must have known he was late as he wielded the heavy bus at high speed around the twists to Ross; so much so, that I couldn’t relax and I was relieved to get out.

Ross is a pretty town, and I wandered its near deserted streets after shop closing time. I needed to find a bank to get out some drinking tokens. It didn’t take too long, although my bank was the last one I happened upon. For some strange reason I don’t even understand myself, I was determined to find my bank even though I knew I could get cash out of any of the others. I broke into the notes to buy post cards for Nicole, Cherie’s eldest daughter and MR, her youngest child, Morgan-Rhys. I had promised Cherie’s children that I would send a post card to one of them every day, so that was a mission I had successfully fulfilled on this first day.

The weather was still beautiful so I called into a pub, ordered a pint of Strongbow and a cigar, and went out the back to the beer garden I had seen advertised on a board at the front. It was really more of a yard and I settled at a table in an elevated and ‘decked’ area that was half completed.

Sitting there with the yard to myself, sadness came upon me, and I suddenly missed Cherie being with me. I thought of her as always, sitting, not opposite, but to my left forming a right angle so she could be on my ‘good side’. I am completely deaf in my right ear and have been since the age of four when an undetected dose of mumps apparently put paid to my stereo perception for life — nerve deafness the doctor had told my mother. As a child of the fifties, it was a foregone conclusion that my tonsils and adenoids would be whipped out — everybody’s were in those days when ‘vestigial’ meant useless. This was supposedly to stop the spread of any future infection to my other ear. Unfortunately, there is no cure for nerve deafness and no hearing aid that will work: you can’t amplify nothing.

I loved the fact that Cherie had switched on to my disability very early in our courting days, and she always remembered where to stand and where to sit so I could best hear her. It was one of those things that showed she loved me and how she cared, not through an occasional act, but all the time, whenever we were together. I rarely caught her out and hardly ever had to remind her — when I did, she was usually under the influence of alcohol. Naturally, few other people are as aware of this as Cherie. It is usually up to me to manoeuvre myself into positions where I will be able to hear what’s going on.

I used to be very embarrassed about my deafness, but these days I will usually own up straight away; indeed, I will take the initiative and ask, ‘Do you mind if I sit here? I’m a bit deaf you see and I won’t be able to hear if I sit anywhere else.’ Hardly anyone objects.

And, if I’m walking along the street with someone, I’ll nimbly skip around to make sure they’re on my ‘right side’. It usually works, although I had a strange experience with a friend of my brother’s in Tewksbury. Talking to Gerry I found him on my wrong side, so I skipped behind and around him. We chatted for a while, but soon he was on the wrong side again. I did the skipping manoeuvre again but within seconds, we were wrong once more. Patiently, I skipped around to Gerry’s right hand side. Then, he did the same thing again.

‘What the hell are you playing at?’ I wondered in mock anger.

He replied in his Gloucester accent, ‘I’m stone deaf in me right ear — what are you playing at?’ Touché!

As I sipped my cider and puffed on my Hamlet cigar, I gazed over a vista that was not impressive — an angular landscape of roofs and house extensions met the sky while beer barrels and crates cluttered the foreground. Cherie’s absence on this journey took me back to a trip we had taken together two years previously. The motorbike, a 1989 Honda VFR was not bad as a touring bike, but we had it loaded like a pack mule. We were biking from Merthyr to the Costa Dorada in Spain via the west coast of France then through the Pyrenees, later planning to meet up with friends at their hired villa near Gerona. The load was significantly increased because we were planning to camp. The back rack was piled high and held in place with the ever-trusty bungees. The back seat had throw-over panniers filled to capacity and I could feel Cherie, dressed like Darth Vader, clumsily trying to cock her leg over the saddle and the huge stack of luggage. All her weight pushed down on the left side foot peg and I struggled to hold the bike as my rather inadequate short legs barely reached the ground. To make matters worse, the lead from her intercom was plugged in and now tried to tangle around every possible projection like an unwanted Russian vine. But she carried on with grim determination and a few expletives. There were so many things I loved about her and, as I sat there on the decking, my tears tried in vain to fill the void.

There was no life in Ross; so, having taken a few photos earlier, I just needed to get some food before heading back to the campsite. I ambled into a quiet covered mall and sauntered into the supermarket to get a few items including wet wipes. I had been sweating profusely all day and I would have welcomed something to freshen me up a bit as I rode along. I then tracked down what was to be the first of many chip shops on my journey and sat under the covered roof off a thoroughfare to enjoy them soaked with curry sauce. It must have been good. One man passed, looked me over and soon appeared with a carbon copy meal that he tucked into on the next bench. I don’t think he fancied me — it was my meal that got him going.

I caught the bus back to the campsite feeling relieved that my leg still seemed to be OK. In the tent, I phoned my mum who told me there had been horrendous and prolonged thunderstorms where she lived in Gwent, and indeed elsewhere including Devon and, nearer to me, Hereford, just ten miles up the road to the north. There was nothing here, so I had been lucky in some respects. It was now eight o’clock and time to get into the pub at the end of Day One. Tuesday night in a backwater, it was bound to be quiet, but I had a pleasant chat with the bar maid and an engaging conversation with a bloke who worked in the sewage farm business. It was very interesting talking to him, and I remember him telling me, that, most of the South Wales coast was now fairly well served with sewage treatment works and that many new plants had been built in recent years. I’m sure the ‘Surfers against Sewage’ would be pleased.

I turned in at about half past eleven and fell into sleep with a troubled mind. What would my leg be like when the morning came?

The Ride: Merthyr to Ross Distance: 41 miles.

Thanks for reading Cambria Stories! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

Serialisation of Hill’s Ups and Downs by Tony Hill with permission. The book is published by Cambria Books and is available to buy HERE.